As told to David H. Lyman, by Karen Sharpe.

Photos byKaren Sharpe

This story appeared the February 2022 edition of Caribbean Compass Magazine.

It was November 20th, 2021, and I had just arrived in St. Maarten on a Southerly 534. After the

1,700-mile voyage from Newport, Rhode Island, the crew and I were congratulating ourselves for completing a trouble-free voyage.

Then we heard about Lappwing, a boat that had just been towed into harbor. There was a story to be told, and seeing as it’s my job to tell stories, especially about boats and voyages, I went to work.

Lappwing and her crew, a couple on their first offshore voyage, had departed from Hampton, Virginia, heading for Antigua. Word on the docks was that some 550 miles north of the islands Lappwing had gone to the assistance of a disabled boat that was part of a rally fleet. In responding, they wound up with contaminated fuel and a broken rudder that threatened to fall off and flood the boat. They limped into St. Maarten in search of repairs. (See story on page 21.)

I spoke with Lappwing’s owners, Roy and Sharon Lappalainen. Roy also sent me contact information for Karen, one of the crew on the disabled C&C 121 that they assisted.

My conversation with Karen tells a more complete story of problems encountered and solved. Karen read and made corrections to my text. Her story provides lessons for us all — crews, boat owners, skippers and rally organizers. I have used her words where I can, then compressed information to save space.

“Why not a yacht, we thought. My fiancé, Martin, and I (retired) have been traveling and exploring North America in a motorhome for the last three years,” Karen began. “So why not a yacht, we thought. We go online to Find-a-Crew, and there’s a boat owner looking for crew. We sign up and fly to Hampton, Virginia, to find we are part of a yacht rally to the Caribbean, a group of some 70 other boats and 300 people, all heading offshore to the islands.

“Two days prior to our arrival, we hear from our 75-year-old owner/captain that our fourth crew member, an experienced sailor, ex-marine, and someone who had helped the owner sail his boat to Virginia, had suddenly departed earlier that day.

“Martin and I had never been to sea before so we knew we needed a fourth crew member. We searched the internet and on short notice found a guy who was able to fly up to join us. He was a 25-year-old sailor who’d been living on his own boat for the last six months. He’d taken a few classes and had been hiring out as crew for short deliveries up and down the coast. I don’t think he had any offshore experience. Not like this voyage.”

Most of the owner’s sailing experience had been on the Great Lakes, with some coastal cruising and racing on the East Coast. Karen said this offshore trip was a first for everyone on board.

The boats in Karen’s rally had been advised to depart two days earlier than the planned November 1st, 2021. “The weather was changing,” Karen told me. “A front was approaching. It was recommended we all leave to beat the storm. We had enough time to provision the boat but there was no time to get out into the bay and practice reefing, changing sails, man overboard drills, use of the VHF radio, steering or cooking underway.

“Most of us left on October 30th, but it wasn’t like a race with everyone lined up. Boats left when they were ready.

“Conditions were okay on our departure and remained that way most of the way down. There were squalls where the wind did blow up into the 30s, but there were no storms. There were a lot of calm spells and light winds.”

Karen and Martin were aboard a C&C 121, a 40-foot sloop. The design, a family club-racer/cruiser, was never really touted as an offshore passage-maker. Her fuel and water tank capacity (according to specifications for the design, 35 gallons and 80 gallons respectively) were not ideal for long voyages with multiple crew. Otherwise, Karen said, the boat was comfortable. There were two private cabins, the one forward where the owner slept, and the one aft for her and Martin. The new guy slept on the settee in the main cabin.

So, off they went, across the Gulf Stream, out into the Atlantic. This was “learning on the job” as the new sailors were getting used to sailing, navigating, trimming sails, reefing, living life on an angle. “We didn’t use the mainsail at night for the first few days until we had a better understanding of sail management.” This C&C, I’ll call her Odyssey, had a main with slab reefing and a jib of unknown lineage on a furling drum on the headstay. There was also a gennaker, stowed in its bag on the foredeck. “It wasn’t until we were far out at sea, in lighter wind, that we got to rig it for the first time. The owner led us through the procedure of assembling the sail and hoisting it, but we had problems getting it completely furled, so for three evenings in a row we had to it take it down and stow it in its bag, which we lashed to the lifelines at the bow. Two mornings, we got up to find the bag had opened and the gennaker was streaming alongside the hull in the water. After the second time we bagged and stowed it never to be used again.” Odyssey was a few days into the voyage when the crew noticed that the solar panels were not keeping up with the boat’s electrical demands: navigation instruments, lights, autopilot, refrigerator and freezer. So they ran the engine for a few hours each day to charge the batteries.

The 35 gallons in the C&C 121’s fuel tank are enough to motor for about 50 hours. Running the engine for two to four hours a day to charge the batteries would use up all the fuel over a 15-day voyage. Karen said that the rally coordinator recommended carrying enough fuel to motor at least a quarter of the trip, “So we had another ten gallons in plastic cans.”

There was a large swath of calms extending from 200 miles south of Bermuda to 24 degrees north, before the easterly trade winds filled in. Everyone heading from the East Coast to the Caribbean last fall wound up motoring for a few days. (The rally director told me he’d put 100 hours on his engine on the way down.) We did as well on the “other rally” on our way down from Bermuda.

By mid-voyage, Odyssey was already low on fuel, as well as water. They had only just begun to use their 1.5 gallon per hour watermaker, so had not replaced any of the fresh water in the tanks.

Day 8 - Halfway to the Caribbean

“On the morning of our eighth day at sea, we couldn’t get the jib to completely unfurl. The wind was 20 knots, gusts to 25, so we were doing just fine and we just kept sailing. Around two that afternoon we heard a loud “SNAP!’ The jib and headstay came down, off to the starboard side into the water. The reefed mainsail was up, so we were still moving, the jib trailing along the side. The owner managed to get the boat turned into the wind and the crew dropped the main. Martin and the new guy went forward to begin hauling the sail and stay onboard.”

“The wind was still pretty stiff, so parts of the sail would catch the wind and lift up out off the water, making it difficult, if not dangerous, to pull on deck. The sheets, still attached to the sail and the boat, were also whipping around.

“As the sail came in, the men secured it to the lifelines. But we were on a 40-foot boat with a 50-foot sail and headstay. There was still a lot of sail left, so the men draped the remaining half over the top of the dodger, covering the solar panels, with a good 15 feet drooped over the port quarter. It stayed that way for about a day.

“The men retrieved the jib sheets, coiled them and tied them off to a cleat up forward. “A few hours later, the engine just quit and wouldn’t turn over. Evidently, the coiled sheets came loose and fouled the prop. The shaft must have locked up in the transmission, for we couldn’t shift back into neutral to restart the engine.

“While all this is going on, I’m below at the nav station, the owner is steering, shouting instructions, Martin and the other crewman are forward tying off three halyards to cleats on the bow to secure the mast. I asked if I should call a Mayday and the captain instructed me to get on the VHF and call Pan Pan — whatever that is.

“‘We are not sinking,’ he tells me, ‘so it’s not a Mayday call.’ I call, then call again. Ten minutes go by and there’s no response.

“Why isn’t anyone responding? I’m thinking. Of course, without using the mainsail at night for the first few days we had fallen behind the rest of the pack. We were all alone out there in the middle of the ocean. We hadn’t seen another boat for two or three days. Now I’m getting scared.”

Calling for help

“The guys were busy so I had to find another way to tell people we were having problems. Satellite email took too long and I hadn’t yet realized that there were SOS buttons on the Navionics devices, another training gap of a rushed departure. I remembered I had emailed my sister in California before we left. She had all the emergency and rally contact information, just in case.

“I called her on the sat phone. When she answered, I said, ‘This is a Mayday. No, I’m not kidding. You need to call the rally shore support number I gave you. Tell them we’ve lost our headstay.’ But all she could make out was a garbled ‘Mayday.’ So my dear sister, who lives in San Diego, calls her local Coast Guard, who calls the Coast Guard in Florida, who hands the call off to the station in Puerto Rico.

“Less than hour later, I get a call by one of the Coasties in Puerto Rico, but his accent is so thick I can’t understand a word he’s telling me. I’m sitting there, looking at a wall of radios and instruments. A few of them have red SOS buttons. So I begin pushing them.

“Within minutes, I get another call from the Coast Guard. They have relayed a message to the rally shore support team. Soon after, I have a flurry of emails from their emergency response team. Thank God! One message saying they have found a boat nearby, a Leopard 48, also in our rally. They will divert to assist. They should be here before morning.”

That night the Leopard 48 repeatedly attempted to contact Odyssey on VHF, but was too far away. But another boat, Lappwing, heard the calls and responded.

Lappwing had left Cape Henry on November 1st. Lappwing called Odyssey on VHF and said they could be there in a matter of a few hours.

“Lappwing found us before dark, drifting, no headstay, no jib, a fouled prop, and no engine to charge batteries, low on fuel and water. We’d already turned off all electronics and refrigeration.”

The two boats chatted on VHF. It was still blowing 20 to 25 knots, and the seas were big so nothing could be done that night. Without headsails, Odyssey was unable to heave-to, so spent the night drifting under bare poles. Lappwing’s skipper elected not to heave-to in order to try to match Odyssey’s drift rate: Odyssey had no AIS and he was worried about losing sight of them in the night.

Karen picks up the story. “For the next two days, we had regular Iridium emails from the rally emergency support team and advice from the professional skipper on the Leopard 48. He advised us on everything from battery charging, chafe management and relieving jammed transmissions to making sure we all got enough rest, food and water so we avoid making mistakes and bad decisions. They were experienced, calm, and knowledgeable and kept us safe and sane until we were safely underway again.

“Next morning the Leopard 48 arrives and motors to meet us and Lappwing. Conditions are still rough, winds in the 18- to 20-knot range, so sending someone over the side to free the prop is out of the question. The rally people and Chris Parker at the Marine Weather Center advised we sail east toward more settled conditions, so all three boats hoist a reefed main and off we went in search of calmer conditions.

“With periodic VHF chats, we headed east. That night, with no compass light, no nav instruments and just the anchor light at our masthead, we hand steered with two-hour watches, following the Leopard 48’s stern light in the darkness.

(Continued at right . . . )

A Comedy of Errors

& Lessons To Be Learned

A Green Crew in the Salty Dawg Rally Experienced Trouble in The Middle of the Atlantic. Two Yachts Divert to Assist. Emergency Avoided.

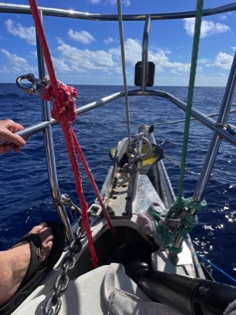

All is well, until mid-Atlantic, 550 miles from anywhere, the headstay parts and is down, no jib, prop fould, almost out of water and fuel, batteries near dead. HELP! Photo by Karen Sharp.

LESSONS LEARNED

Karen and Martin certainly had a lot of “experiential learning” crammed into their two-week delivery. What can we learn from their story? A lot.

The Offshore Boat

You could write a book about the right boat to take to sea on a long offshore voyage. Don Street did, all 700 pages: The Ocean Sailing Yacht, published in 1973. I have a copy and refer to it on occasion, to the point where I don’t know where Street leaves off and my own experiences take over. Other authors have added their voices over the years, each from their own experience.

This C&C was perhaps not the ideal offshore boat for a 1,700-mile, two-week voyage, with fuel capacity being one issue. What happens if you lose the ability to sail? I’d advise carrying enough fuel to motor a third of the way; halfway would be better. Six additional six-gallon jerry cans strapped down on deck would have allowed them to run the engine more to keep the batteries charged and to motor though calms. Know your boat’s fuel consumption at various RPM.

The Rig

I love a sailboat with more than one headstay, be it an inner forestay for a staysail, or a Solentstay — two headstays attached to the bow, one with a light-wind genoa, another with a high-cut yankee. Should one headstay fail, you still have a second stay to secure the mast, as well as a jib to sail with or heave-to.

With no jib, Odyssey was unable to work to windward. With a compromised mast, held up forward by jury-rigged halyards, putting the wind aft the beam was their only option.

Before a bluewater voyage, inspect the standing and running rigging, preferably having it done by a professional rigger.

Pre-departure preparation

The time spent in preparing a boat and new crew for offshore is critical. Provisioning and stowing for a month-long voyage to and through the islands can take two days. Training a new crew on raising, lowering, trimming and reefing various sails should take a day. Throw in a man-overboard drill. A thorough briefing on safety, communications, navigation, shipboard living, and abandon-ship procedures — all these can take a day. Don Street recommends taking novice crew for day-sails in heavy weather for practice, so the first bad weather encountered isn’t offshore.

When to depart

If you’re not ready to depart, don’t. Going off half-cocked has ruined many a voyage.

Experienced delivery captains on last fall’s voyage south told me, “Don’t give me waypoints and a departure times. Give me the weather details and I’ll make my own route and departure date.” Too many new owner-skippers turn over the sailing of their boats to routers and technology. They substitute convenience and the ease of push-button operation for good seamanship.

It’s worth noting that Lappwing left on November 1st, the rally’s original starting date. Although Odyssey left two days earlier, anticipating an approaching front, Lappwing reported fairly light winds on departure.

The skipper

Any skipper heading offshore on a long voyage had better have made a similar voyage before, on their own boat or someone else’s. If not, then hire a pro skipper to come along as a mentor. They’ll get your boat there and teach you a great deal in the process. You can read all the books, take all the classes, watch hours of YouTube video, but nothing replaces experience at sea.

The Crew

On a voyage like this, the crew should have made a couple of offshore, deepwater voyages previously. Many insurance companies want to see this on your crew’s sailing resumes.

Also, know if your crew gets seasick. A few hours into the voyage and the crew become incapacitated, you are now on your own, in addition to tasking care of the handicapped crew.

I could go on... but I won’t.

Captions: Karen nat trhe wheel. The men working on the headsail. Karfen and Marton. Halyards were tied off at the bow to replace the forestay. Headsail draped through cockpit. The Leopard circled us with videos running to document and determine what the problems were. Headsail draped through cockpit. During a squall, that center area filled with rainwater and two of the crew used it for a bath!

( . . . . Continues fromn left.)

“What is really cool, is this is our first sailing experience,” she added with a chuckle. “Here I am, a 50ish-year-old retired doctor looking for a little excitement. This is my first voyage on a boat, any boat. Martin, also retired, and I have been traveling North America in a motorhome, so many of the systems are the same — batteries, solar, septic, water pumps, 12-volt refrigeration, propane stoves, living in confined spaces. But this was perhaps a little more than we expected.

“At 5:00 in the morning, Day 10, I came on deck for my watch. The sun was just rising and it was relatively calm. All three boats were drifting, all within sight of each other. A lazy swell was rolling but very little wind so I radioed the other boats that I was going to take a peek at the prop. I took my mask, held onto a line and slipped over the side.

I wanted a bath anyway. As I looked under the stern of the boat, the water crystal clear, I could see both jib sheets were wrapped around the prop. With the boat rolling, I did not feel safe diving below to unwrap the lines. The new guy’s a young buck, I’ll let him do that.”

Later The new crewmember dove under the boat and within a few minutes had the sheets unwound and cut free. With the prop now free, the crew could move the shaft, free it from the transmission, shift into neutral, and start the engine.

Fuel transfer

“While we were busy with clearing the prop, the Leopard 48 deployed their dinghy, motored over to Lappwing, picked up two jerry cans of fuel, and returned back to their boat. The skipper asked us to drift a long line downwind to him, tied to a seat cushion. He picked it up, tied it to his dinghy, then tied one of his lines to the dinghy, now filled with fuel cans, jugs of water and dry bags of canned goods, boxes of milk, bags of rice. We pulled the loaded dinghy over to our boat. I climbed in and handed 40-pound jerry cans up to the men on deck. But now, the boats had drifted too far apart for them to pull their dinghy back, so we untied our line and let the dinghy drift. The Leopard 48 motored around and with a boat hook the skipper picked up his line and secured his dinghy.

“The mission accomplished, our engine running, the prop free, we all waved goodbye and headed off to Antigua.”

Three hours later, Lappwing’s engine died. Roy changed the filter, then cleaned the filter bowl, all to no avail. “All that rolling around that night under bare poles must have stirred up some crud in the fuel tanks and fouled the lines,” Roy said. Then Lappwing’s rudder failed and she diverted to St. Maarten for repairs.

Odyssey’s adventure wasn’t over either. Soon after leaving the other boats, the crew still had issues. “The autopilot kept turning us in circles, so we ended up hand steering for three days until we made landfall.”

After reaching the tradewinds, it became evident to the crew that without a jib there was no way Odyssey was going to sail to Antigua. Also, with still limited fuel, there was no way they were going to motorsail those last 500 miles. They diverted to the US Virgin Islands.

“We pulled into Charlotte Amalie late on the afternoon of the 15th day, too late to clear into Customs and the health authorities. So we anchored. Next morning we launched the dinghy, but the onboard wouldn’t start, so we hailed someone for a ride to clear in. With that done, we returned to the boat one last time to help the owner get safely into a slip at the marina.”

What are you going to do next? I asked.

“We have a few options, but even after everything we just experienced we realized we both love sailing, and want to learn more and find another boat in the Caribbean. We’re even thinking of getting our ASA sailing certification.”