Story by David H. Lyman

This article appeared in SAIL Magazine

March 2023.

It was March, and I’d made it through another Maine winter. The warm trade winds in the West Indies were calling; time to go sailing. But not just any kind of sailing. Few places on the planet have such a devoted, diverse, and downright joyful yacht racing season as the island of Antigua, and it was calling me back, as it always does.

When my family and I were living aboard our Bowman 57, Searcher, Antigua was a favorite destination, and it remains tops on my list. While far from the perfect tropical island—it’s relatively flat and dry—it’s perfectly placed in the middle of the Leeward Islands, an easy beam reach south to the larger Windward Islands of Dominica, Martinique, St. Lucia, and St. Vincent, and the Grenadines all the way to Grenada, then Trinidad. Or, ease the sheets and it’s a full day’s sail north to St. Barths and St. Martin, then overnight to the BVI, all downwind.

With its beautiful English Harbor and Falmouth Bay, the island is also well suited for sailboats and sailboat racing. In the waters just offshore there’s enough sea room to establish two challenging racecourses to test boats and crews, and the season begins gathering momentum as early as November, when scores of cruising sailboats taking part in the annual Salty Dawg Cruising Association’s Caribbean Rally arrive after passages from ports along the East Coast and Bermuda. The Antigua Charter Yacht Show in early December is followed by the Nelson’s Pursuit Race, the Budget Marine High Tide Series, and a string of holiday get-togethers. Then in the New Year it’s the Round Island Race; the RORC Caribbean 600 in February; the Superyacht Challenge in March; and the Antigua Classic Yacht Regatta in April. Antigua Sailing Week in early May winds up the season.

“It’s the boats that draw them here,” Jane Combs told me. She and her late husband, Kenny, founded the Classic with a few others. “The racing is just an excuse to gather.”

As Combs recounted it, the Classic’s roots started in the late 1960s, when at the end of charter season, captains from the Nicholson fleet challenged each other to a race. The course: the Dockyard to Deshaies, a small French harbor village on Guadeloupe, 45 miles due south. A post-race party naturally followed ashore, then a race back the next day.

In 1967, Desmond Nicholson, Howard Hulford of Curtain Bluff hotel, Peter Deeth of The Inn at Freeman’s Bay, and the Antigua Hotel Association put together Antigua Sailing Week—a series of races around Antigua, with a BBQ on a different beach each night. This somewhat irreverent event morphed into something more dignified and formal with a costume ball and more serious racing around the buoys just outside English Harbor—all to attract more guests to the island.

The Classic broke away from Antigua Sailing Week in 1987 when one of the big boats driven by Uli Pruesse had to make an emergency maneuver to avoid sinking one of the racing bareboats. Later that day, Pruesse, Kenny Coombs, captain of the Nat Herreshoff-designed schooner Vixen II, Tony Newell, owner of the ketch Meroe of Kent, and Tony Fincham, owner of the schooner New Freedom, met in Aschanti’s cabin and instigated the Antigua Classic Yacht Regatta.

“It’s the sun, the steady trade winds, the blue sky and warm, blue water that brings me back each year,” one of the European yacht owners told me. “This is my twelfth Classic.”

The Classic attracts a unique kind of sailor, I’ve discovered. They are not your gung-ho, team-bonding racer-types.

“Classic is more laid back,” one skipper told me, “a bit more genteel.”

Just being here, feeling these elegant, well-maintained yachts power through the blue seas, the warm spray over the bow—what more could you ask for? As Combs said, “It’s the boats.”

Force 7 winds led to the cancellation of the singlehanded race on Thursday, but The Concours D’Elégance competition went on as planned. Since it’s all about the boats, a panel of judges awarded crews and skippers for how well they cared for and presented their yachts. Varnished trim, scrubbed decks, coiled lines, polished brass, cabins neat and glowing—it all counted. Prizes were awarded, toasts made, and rum flowed at the party that evening on the yacht club lawn.

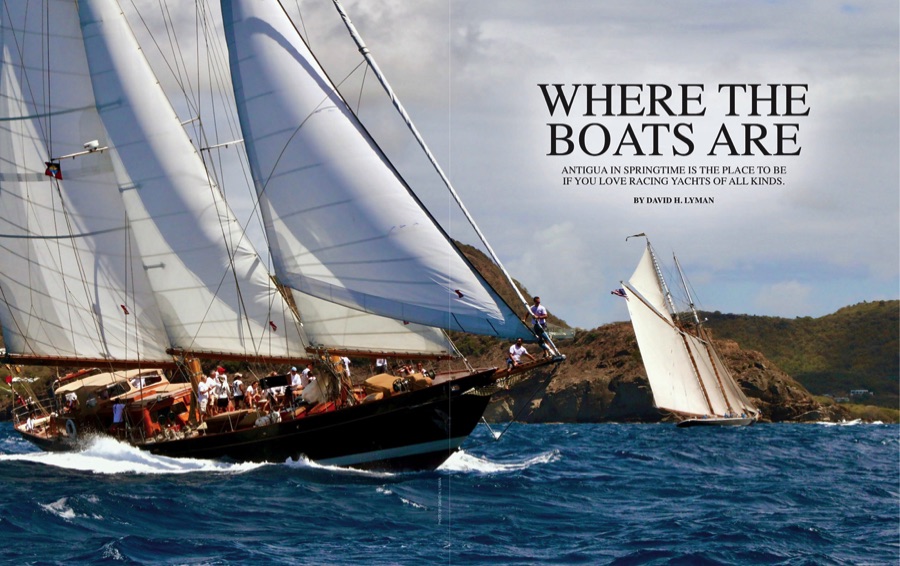

The next morning, winds were east at 20-28 knots, gusting to 35. Seas were 5 to 12 feet, some larger and breaking. No one came ashore dry, as spray would often engulf entire boats. More than once, the bowsprit of the 141-foot schooner Columbia was buried, the bowman hanging on to a forestay for dear life.

The challenge to watch was between the two black schooners, Aschanti and Columbia. The Gruber-designed, Bermudan-rigged staysail schooner Aschanti was built in 1954, and Columbia, a gaffrigged replica of the original Grand Banks Fisherman, was built in 2009. Try as he might, Columbia’s skipper Seth Salzmann could not best Aschanti’s ability to work to windward.

“Columbia’s large main will drive her faster on the downwind legs,” Seth said. “We just couldn’t catch and pass Aschanti. The downwind legs were not long enough. We never had enough time to beat her to the next mark.”

On Saturday, winds remained east but down to 18-25 knots. Swells from the previous day’s winds continued, so it was another wet race around the buoys for all crews. On Sunday, winds and seas were still east but down to a comfortable 15-18 knots. The fleet sailed a course outside Falmouth and English harbors, a pleasant romp in moderate seas.

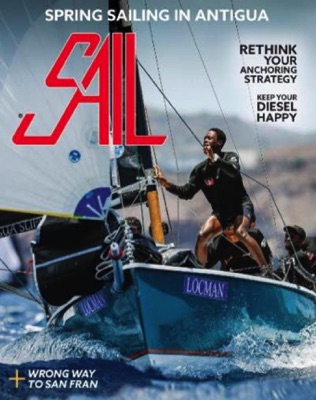

That evening, some 300 owners, crews, organizers, volunteers, and sponsors gathered at Lucky Eddie’s event arena for the prize giving and congratulations. Admiral Kenny Paterson, the yacht club marina manager, presided (in period uniform), as winning crews gathered onstage to receive Locman wrist watches, silver bowls, bottles of Mount Gay rum, and the applause of their fellow classic yacht sailors.

Now, For Some Serious Fun

A month later, Antigua Sailing Week got underway for its 53rd year. Slick racing yachts and crews of all stripes began arriving a week early. The yacht club was abuzz as I walked the docks to chat with racers, and the teams stripped their boats of anything not absolutely necessary for racing. Sailbags, toolboxes, cushions, galley gear, docklines, fenders—all were piled high on the docks by each boat

Over at the Dockyard, the bareboat fleet was assembling, stern-to. Nearly 40 bareboats were entered this year, 16 of them from KH+P, a German chartering agency. Organizer Hartmut Holtmann said he’s been putting EU teams together for Sailing Week for 20 years.

“Some years we have as many as 30 boats. It’s partly a cruising vacation with some fun racing thrown in.” Holtmann’s crew this year numbered around 80, mostly from Germany but with teams also from Italy, Spain, the U.K., and Brazil.

On Saturday, things got underway with the Peters & May Round Antigua Race. Then followed five full days of flat-out around-the-buoys racing on two courses just outside English and Falmouth harbors. Each afternoon, when the boats had returned and rinsed off, crews, owners, and officials were greeted with buckets of Carib beer and tots of Dockyard Rum for awards presentations on the yacht club lawn—parties that predictably lasted well into the night.

Thankfully, Wednesday was a lay day—time for a break and for teams to get off the boats and gather, this time at Pigeon Point Beach for fun and games, dinghy races, swimming, and a tug-of-war.

Last year’s regatta saw a multitude of classes encompassing pro racers, a sport boats class, performance cruisers, multihulls, and bareboats. In total, more than 800 sailors were there: paid pros, amateurs, first-timers. There were club teams, all in colorful, matching shirts, from Europe, the U.K., U.S., Brazil, Antigua, and the French West Indies.

As a counterpoint to the Classic, Antigua Sailing Week draws a different kind of sailor and seems rather more serious from a competition standpoint.

“Sailboat racing is a very complex intellectual sport,” said San Francisco-based sailor Bratz Schneider, who had chartered a Beneteau Oceanis 46 from the Moorings and invited along his regular racing team for a vacation. “In addition to being physical, it’s incredibly cerebral. There are splitsecond decisions that need to be made about each tack or jibe. The boat needs to be driven and each crew member needs to know and perform their role. There are tactics and the rules to contend with. It’s a game of geometry as boats come together, jockeying for advantage rounding a mark, avoiding a collision, setting spinnakers. It’s precision.”

Sailing Week ended with a grand flourish of prize giving, more silver bowls, more Locman watches, and copious showers of champagne. It closed out a grand season of racing in the tropics, and once again I was reminded why Antigua is still my favorite island.

David H. Lyman is a sailing photojournalist who has covered New England and the Caribbean for more than 20 years. He writes from his home in Camden, Maine. Read more at dhlyman.com

The 2023 Antigua Classic Yacht Regatta is April 19-24. More at antiguaclassics.com.

Antigua Sailing Week 2023 is set for April 28-May 5. More at sailingweek.com.

Staysaikl schooner Aschanti, Day One of fhe 2022 Anigua

GETTING IN ON THE ACTION

There was a time when you could arrive in English Harbor, walk the docks, and find yourself crewing aboard a large schooner, racing all day and sleeping on sail bags on deck at night. Romantic as that sounds, today there are many more options for getting in on the action at the Classic and Antigua Sailing Week.

If you’re cruising on your own boat in the Caribbean, you can enter either event in divisions just for cruisers. Sarah Schelbert, a solo sailor from Germany now living on her boat in Carriacou, entered her 36-foot, Alan Gurney-designed sloop Alani in the Classic after restoring the boat and sailing her to the Caribbean from Guatemala. It was Sarah’s first-ever regatta, racing with a novice crew of friends and relatives. She won her class.

On a whim, a Canadian nurse, Jocelyn Mclaren, bought a C&C 38 called Belafonte in Virginia in the fall. With a few female nurse friends, she got the boat to Florida, the Bahamas, and finally the Leeward Islands. It was “a work in process,” she said. “We were fixing things as we went.” She reached Antigua in time to enter Sailing Week. With a few friends and a new-to-her boat that needed constant repair, Mclaren and her team won the final race of the week, placed seventh in their class, and earned the “Best Female Crew” award.

You can charter a tricked-out, dedicated racing machine or a standard bareboat from Dream Yacht Charter, Moorings, Sunsail, and others. You can pay to climb aboard one of Global Yacht Racing’s special racers for your first experience around the buoys. Company founder Andy Middleton said that his sail race training school based in Cowes, U.K., had three Beneteau 47.7s racing at Sailing Week, each crewed by teams of strangers.

“We take them out for a few days before the races to get them familiar with the positions and maneuvers, then it’s full-on racing,” he said. “We have teams race with us in all the regular U.K. and EU regattas. And yes, you can sign on by yourself, even if it’s your first time racing.”

Chris Jackson from Southampton, who with his wife, Lucy, runs LV Yachting, a racing boat charter agency, had brought Pata Negra, an IRC 46, to Antigua to be chartered by a team of U.K. sailors from the Itchenor Sailing Club. “This is the second time we’ve raced aboard Pata Negra,” one of the team members said, “and we are just getting to know her. We won two firsts and a second.” The club had also chartered a second boat, a Pogo 12.5.

Each of Antigua’s events has a crew request and availability board on its website, and there’s a bulletin board at the yacht club where sailors and skippers communicate. Or you can do it the old-fashioned way: walk the docks asking if anybody needs crew.

At Pineapple House, I met Rich Sims, a solo sailor from the U.K. who had just sailed into English Harbor on his own boat looking to crew on one of the large Classic boats. Rowing his dinghy ashore one morning before the race, he passed Aschanti’s bow and hailed a crew member who referred him to the skipper. Rich talked his way into a job for three days minding one of the running backstays.