The Nicholson Sisters

Of English Harbor, Antigua

© 2022 David H. Lyman

This story appeared in the March 2022 edition of Caribbean Compass magazine. It ws this story that won me second place in the 2022 Boating Writers International aannual compeition.,

My sailing buddy Larry and I pulled into Falmouth Harbour two years ago and anchored off Pigeon Beach. We had just completed an offshore voyage from Maine to Antigua. We were hungry to get ashore. I had an assignment from Caribbean Compass to cover the Antigua Charter Yacht Show starting in a few weeks and needed a base ashore. Larry, who knows the island and everyone there, knew just the place.

“Pineapple House!” he shouted as we launched the dinghy. “Wait ’til you meet Libby Nicholson. She’s from the family that started the charter industry in the Caribbean.” Larry’s 54-foot sloop, The Dove, is one of the charter boats Nicholson Yacht Charters represents.

We jumped into the RIB and sped to the dinghy dock at the Seabreeze Café next to the yacht club. Five minutes later we were climbing the stone steps to Pineapple House.

“This is where all the yacht crews hang out,” Larry told me, “when not on charter or racing.”

A brown wooden gate with a white pineapple nailed in the middle swung open and there I saw a West Indian cottage colony, ten individual cottages and the Great House, scattered up the hillside that overlooks English and Falmouth Harbours. The Antigua Yacht Club and its docks full of mega-yachts were just below.

“Great view,” I told Larry. Then Libby hove in sight, flying down the cascading stone stairs to embrace the two of us with a hug that would have broken the backs of lesser men. Libby, after 60 years of living on and off this island, is still one of the major characters in English Harbour society. She’s an energetic woman of indeterminate age with a ready smile and an artist’s flair. An accomplished silversmith, architect and interior designer, Libby makes her own statement with silver bracelets dangling from both wrists and colorful fabrics draped over her statuesque form, flowing as she moves.

“Let me warn you,” Larry whispered. “This may be a B&B, but the second B is not for breakfast, it’s for booze.”

We were just in time for Libby’s early evening soirée. Libby went on mixing up a few gallons of rum punch and chatting away, full of questions of our delivery. Most evenings, Libby holds court on the veranda of the Great House.

“It’s a tradition my grandfather, the Commander, started over 60 years ago,” Libby told us, pouring ample amounts of the local Cavalier rum into the mix. Guests, locals, yacht captains and crews, even a stray journalist, gather here to swap stories, tell lies and share observations of life in the tropics.

The seating area was soon packed, people reclining on colorful cushions, standing in open doorways, sitting on the porch railing or on someone’s lap. It’s here you hear about a narrow escape from the carabiniere in an Italian port, a particular captain who had to marry the daughter of his yacht’s owner, the lavish lifestyle of charter guests, races and romances won and lost. It’s here yacht crews come to get off the boat, take a shower, and sleep in a real bed.

I’d walked into a writer’s paradise, full of characters and stories. The all-female crew from Maiden, of Whitbread Round the World Race fame, had just arrived in Antigua and all eight had moved into Pineapple House. Bedraggled from a 10,000-mile voyage across the Pacific via the Panama Canal, Pineapple House offered them the first showers and horizontal beds they’d seen in months.

“It’s not all yacht crews,” Libby added. “We have honeymooners, travelers, couples, families looking for an affordable vacation.”

At Pineapple House you can rent a private single-room cottage, or a queen-size bed tucked into an alcove on the front porch of the main house, or a single bed in the crews’ quarters.

“It’s co-ed,” Libby explained, then added with a giggle, “Yacht crews are used to communal living.”

The three Nicholson sisters, Dana, Libby and Shelby, were born on Antigua, each barely a year apart. Their grandparents, “the Commander” and his wife Emmie, with two sons, Rodney and Desmond, had stopped here in 1950 on their way from Ireland to Australia on the schooner Mollihawk.

“In 1940, Grandpa found the yacht sitting on a mud bank in Kent while tasked with assembling a fleet of private boats to evacuate the troops trapped on the beach at Dunkirk,” Shelby told me. “After the war he went back and bought the schooner, as much for its silverware, crockery and bedding as the boat itself. Mollihawk was a 79-foot wood schooner, built in 1903. After making her ready for a long sea voyage, the family, which included our dad, Rodney, and uncle Desmond, left Ireland in 1949 to sail halfway around the world to start a new life. They got halfway.

“The family stopped in Antigua, and tied up at Nelson’s Dockyard in English Harbour. The schooner needed repair. No sooner had they arrived than Amber, the calico cat, leapt off the boom and swam ashore. She was in heat, got pregnant and had kittens... that’s when Granny Emmie whispered to Grandpa, ‘Darling, I think we’re HOME!’”

Nelson’s Dockyard had been abandoned for at least a hundred years, roofs falling in, windows missing, shutters hanging off. In the 1700s and into the mid-1800s this had been an important British Naval Base, but was now forgotten. The locals feared “jumbies” lived there, the spirits of dead sailors. The family fixed up the old Paymaster’s Quarters and moved in.

While establishing a home base at the old Powder Magazine at the Dockyard, the Commander was approached by wealthy guests at the Mill Reef Club a few miles to the east. “That’s a mighty fine schooner. Mind taking us for a sail?” That started the yacht charter business in the West Indies in 1950. Within a few years there were a dozen private yachts, most skippered by British captains who took charter parties on a week’s explorations to the islands to the south. Antigua is ideally located in the island chain where the tradewinds will blow you south then north on a beam reach both ways. This opened up the islands of Guadeloupe, Dominica, Martinique, St. Lucia, St. Vincent & Grenadines for exploration.

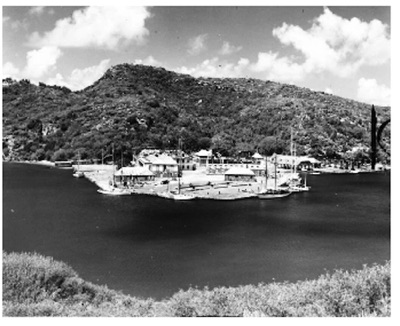

Above: Once abandoned, then the Nicholson girls’ playground, Nelson’s Dockyard, is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Nicholson & Son Yacht Charters Inc. grew into a thriving business, and is today a major name in yacht chartering, with offices in Antigua, Newport, Rhode Island, and Cambridge, Massachusetts, and an office in Blue Hill, Maine, where Shelby works when not in Antigua.

In 1954 the schooner Yankee, skippered by Irving Johnson, sailed into English Harbour on its ’round the world voyage. Onboard was a recent Smith College graduate, Julie Pyle, from a respectable (and wealthy) Connecticut family. During that brief stop Julie met Rodney, and something must have clicked, for when her voyage ended a year later she flew back to English Harbour. Julie and Rodney eventually married, and she became wrapped up in the family’s charter operation.

“Mother was an excellent writer,” Shelby said. “The letters she wrote to clients showed them in words what their upcoming charter was going to offer. She wrote all the brochure copy. PanAm distributed our brochures to travel agents all over the country.”

Then the girls came, one after the other: Dana, Libby and Shelby. Growing up in English Harbour was like “never-never-land,” according to Libby. “We were in the water more than out of it. There were vacant beaches, hills to climb, yachts to sail, fish to catch, games to play. The Dockyard was our playground, with all those buildings either falling down or under reconstruction.”

Restoration of the Dockyard began in 1951, with the Commander in charge. The coral stone buildings, the sheds, and the Admiral’s House were brought back to life, providing a stage for the three young girls and their imaginations.

The girls were not alone. A growing community of English, Canadian and American expats had moved into English Harbour, including a few families of the charter captains.

“So, there was no shortage of children our age to play with. They included Michael and Peter Endicott from Mill Reef, Cary Byerley, whose father ran the 72-foot schooner Lord Jim, and our cousins, the other Nicholsons, Sarah, Chris, Nancy and Celia,” Shelby wrote in a draft of her memoir. “We had wonderful times playing on the hillsides, on the beaches and in the Dockyard.”

In September of 1964 the sisters and their pals were off to Sunnyside School in St. John’s, the island’s capitol. This was the first school to be integrated on the island. Shelby wrote, “Given the tumult surrounding desegregation in the United States in the 1960s, our headmaster, Mrs. Wilson, had integrated Sunnyside School immediately and without question that summer, and that was that. There were no riots, no hair pulling, no angry mothers or fathers or police or undue embarrassment. Life went on as normal.”

“Life was carefree,” Libby added. “Grandpa had taken over the old Powder Magazine and turned it into a home. The floors were teak like the deck of a yacht.” The Commander, Vernon Edward Barling Nicholson OBE, being half Irish and half Australian, was a natural raconteur and loved to entertain. “On Sunday afternoons he held a party for the skippers and crew of the charter fleet, and anyone else who happened to be in town.” The Powder Magazine is still there, across Ordnance Cove from the Admiral’s Inn, but it’s no longer the Nicholsons’. It’s now called Boom, an upscale restaurant, but that’s another story.

By the mid-’70s, Rodney had moved ashore and was running the charter office in Antigua with Julie. Desmond, the more studious brother, turned his attention to the island’s history and anthropology, eventually writing several books on Antigua’s past.

Rodney and Julie had a house with few walls, built on a hill overlooking the Dockyard, a great space for playing. Desmond and his family built a home on the opposite hill.

Julie had been brought up in cosmopolitan Connecticut, and had a degree in philosophy. She wanted more education for her daughters than Antigua could provide at the time, so when Libby was 13, she packed all three of them off to separate private schools in New England.

For Julie herself, life in Antigua was just a bit too parochial. By the mid-’60s, Nicholson and Son was a thriving business, but communication with clients was difficult. Mail took weeks. Phone calls were expensive and reception sketchy. Julie, who had by now become an indispensable part of the charter game, told Rodney she was returning to the States to set up a proper office in Massachusetts, and be closer to clients and her family there.

“I always thought our parents were more like brother and sister than husband and wife,” Libby confided. “But they continued to work well together: Julie in the booking office in Cambridge, where communications were better, Rodney running operations in English Harbour, where the yachts were.”

After private school, Dana went to UMass in Amherst, then transferred to Smith, her mom’s alma mater. “She’s the restless one,” Shelby added. “She’s a fine painter, but has always been drawn to yachts and adventure. She’s off right now on another transatlantic yacht delivery. She loves racing yachts.”

Libby was off crewing on yachts in her late teens, exploring the Mediterranean and the rest of the Caribbean. Grandmother Pyle, on their mom’s side, was concerned for Libby’s future. She insisted Libby acquire skills that would ensure she could earn her own way.

“She sent me off to Katharine Gibbs School in Boston for a year to learn typing and office management.” With new skills, her experience and connections in yachting and chartering, Libby landed a job in New York City at the renowned yacht design firm Sparkman and Stephens. One day, as Libby tells it, “A tall, handsome Canadian yacht captain came through the door to my office. His name was Fred Long, from British Columbia. He came to discuss a new boat for his father, a wealthy industrialist.

“I showed him photographs and plans for Battle Cry, a 47-foot cold-molded racing machine designed by Sparkman and Stephens. How I loved that boat. Well, they bought the boat and immediately changed her name to Indomitable. I, of course came along with the deal. For three years, Fred and I sailed her all over the Pacific, winning race after race. I knew sail trim and racing maneuvers, but Fred was a brilliant tactician and helmsman. We made a great team. He was my ‘super hero.’ I’d become a member of the Long family... well not officially yet.

“I was in no hurry to settle down. I was in my mid-twenties. Life was too exciting. I was still sailing across the Atlantic on deliveries. While in the Canary Islands I called Fred, who was in Vancouver, just to tell him where I was. The connection was poor, and I wasn’t sure what he said, something about a mirage. I asked him to repeat it, and he said ‘Will you marry me?’ Of course I said yes. I was 30 then.”

Two years later, Christie, their daughter, arrived, then Russell, their son. Libby settled into life in Vancouver. After private school, Shelby joined her mother in the Cambridge office, matching clients with yachts and crews an its still at it. She has now joined Libby in Antigua to help out, while Dana is still away, racing through life.

Her kids grown, Libby moved back to Antigua in 2000, to lead a “simpler life.” I doubted that, watching her juggle two phones, a staff of three, guests, and plans for renovating properties in Maine and British Columbia. Soon after arriving back home, she bought the hillside up behind the yacht club. She had a few local fellows knock together a typical West Indian cottage.

“Nothing fancy, mind you. Just two-by-fours, boards and a corrugated tin roof. Leave the windows open. No doors in the doorways. I want the sea breeze to blow through.”

That spring, while she was getting ready to head up to Maine, a crewmember off a yacht asked if he could rent her cottage. She said yes. When she returned in the fall she had another cottage built, then another. There are now ten, each different, each decorated in what Libby calls West Indian chic. Colorful fabrics replace doors, shutters protect what would be called windows welcoming the tradewind breeze, and the décor is mainly seashells. Some cottages have modest kitchens. Most have hot water and all have a veranda overlooking the anchorage. There is still the “Crews Quarters” and half a dozen four-poster beds with billowing white canopies are tucked into alcoves here and there, all very informal. I could move in. I’d spend the season, write stories about sailing the Caribbean, colorful characters, and island life. (In fact, I think I will.)

The Nicholson sisters are holding on to that romantic life of fast yachts, rum punch and boisterous crews ready to spin a yarn.

The Veranda at Pineapple House, the Nicholson Sisters Cottage Colony overlooking English Harbor.

This page, clockwise from top:

Pineapple House’s porch provides views of the yacht club docks — and places to sleep.

Dana, Libby and Shelby on their bicycles in the 1960s. ‘We had wonderful times playing in the Dockyard... life was carefree.’

Libby, Julie, Dana, and Shelby on a family cruise through the Grenadines aboard Staffordshire. circa 1967.