A Christmas Delivery

The plan was straightforward: four Caribbean Islands in four weeks. The execution was not quite as smooth, with many an unexpected pleasure—and a few nagging annoyances—along the way.

Story by David H. Lyman, and Family

LARRY, a friend I’ve known for 20 years, had just dropped anchor in my harbor in Maine. He was returning from a summer in Greenland, heading back to the Caribbean, and he had a question for me:

“You busy this fall?”

“What do you have in mind?” I already had an idea.

“Well,” he said, “how about helping me sail The Dove down to the Caribbean?”

A few weeks at sea, with Larry, on his Crealock 54 expedition-style sloop? I had to give this invitation some serious thought. That took me all of six seconds. But there was more.

“When we get there, how about minding the boat for me while I take off for two months? I need a break. You can invite your kids to join you for Christmas,” he added. “They can help you sail the boat down to Martinique for me.”

And, that’s exactly what we did. With stops along the way. Here’s how it all unfolded.

THE GRAND PLAN

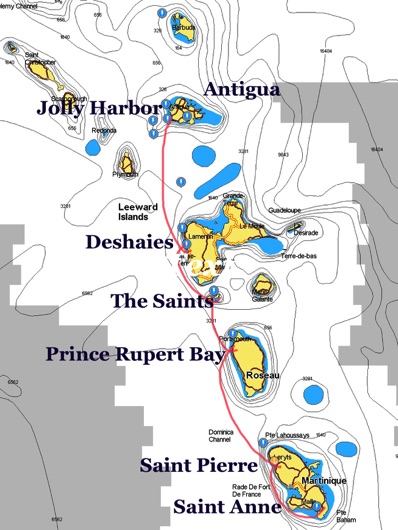

With the fall offshore delivery complete, by mid-December The Dove and were safely ensconced with the hook down off Antigua. My family was aldewasdy onboard, as my finger traces the route along a string of Caribbean islands on the chart. I brief my crew on the upcoming delivery from Antigua to Martinique.

“We have four weeks to get Larry’s yacht from here to there,” I tell them. “We’ll leave Antigua in a few days, hop over to Deshaies on Guadeloupe for Christmas, then make our way down to the Saints for a few days. Then on to Portsmouth on Dominica for New Year’s. From there, on to Saint-Pierre on Martinique, and finally, here, Sainte-Anne at the southern end of Martinique. How does that sound? Four islands in four weeks.”

My crew of three includes my daughter, Ren (short for Renaissance), 21, a junior at Maine Maritime Academy; my son, Havana, 19, off to Solent University in the UK to study marine engineering and naval architecture; and Julie, their mother, who has been sailing with me, off and on, for more than 20 years. All three have flown in to share the Christmas holidays and help with the delivery.

“Can we go ashore this time?” Havana asks. Ten years ago, we made a similar trip down to Bequia on our own Bowman 57 ketch, stopping each night just to sleep.

“This time,” I tell him, “we’ll have plenty of time to explore the islands.”

The water is clear here, in the Pigeon Beach anchorage in Falmouth Harbor. The laundromat is across the street from a farmer’s fruit stand by the dinghy dock, only six minutes away. There’s a small marine store down the road, and a few shops nearby provide bare essentials. The Seabreeze cafe by the mega-yacht dock has Wi-Fi, and they speak English. I could stay here all winter. But after lingering around until a week before Christmas, we have to get going.

After provisioning and taking on water in Jolly Harbour, we motor around to Five Islands Bay for the night. The bay is wide open with a dozen possible anchorages, but it’s the Hermitage Anchorage we head for.

“Go farther in,” Ren shouts from the foredeck. “Get close enough so we can pick up the hotel’s internet.” Behind the beach lies the posh Hermitage Bay resort.

“We’re close enough,” I shout back. “Drop the hook. I’m backing down.”

“Not yet,” she shouts back. “Over there by that ketch.”

“Don’t argue with me. Drop the hook.”

Down it goes, but my daughter is none too happy when she returns to the cockpit. At 21, she already has her second mate’s Coast Guard license. This tension between the two of us does not bode well for the next few weeks.

“I told you. You anchored out too far. See! There’s no Wi-Fi from the hotel.” Ren shoves her iPhone screen in my face. I shrug. Lack of internet does not bother me. I’m from another generation, but for my kids, this is a major inconvenience.

Quickly, things change. There are beaches to explore. Down come the paddleboards. Off they go. These two were brought up on the water—in boats, canoes, kayaks, dinghies, 420s, a Capri 14.4, and for 12 years on our second home, Searcher, our Bowman 57 ketch.

This Hermitage anchorage is one of my favorites. It’s quiet here. Just a few other boats around, four vacant beaches, and the setting sun is spectacular. Jolly Harbour, with all its services, is a 14-minute dinghy ride away. But Wi-Fi there is a bit spotty.

OFF TO GUADELOUPE

“Ren,” I shout, as we finally set forth from Antigua, “can you and Havana get the main up?””

“There’s no wind!” Ren shouts back from the foredeck.

“We still want to raise the main. Now.”

“Why don’t we wait until there’s wind?” Our discussion continues until Ren consents. Small victories.

It’s 48 nautical miles to the anchorage in Deshaies on the northwestern tip of Guadeloupe. As we emerge from the lee of Antigua, a 12-knot easterly breeze carries us out into the Caribbean Sea, with the 3,000-foot mountains of Guadeloupe visible ahead. This stretch of ocean, between the islands, can be boisterous at times. When the “Christmas winds” are blowing at 30 knots and 10-foot seas are rolling in all the way from Africa, these 40-odd miles can be nasty.

Today, however, they’re a delight. There’s enough wind to sail with main and jib. We are making 6 knots, a slight heel to leeward. The sky is blue, the water bluer, and a few clouds float above the horizon. The family settles down. Julie, below, is fussing with cushions and baskets of fruit. The kids are stretched out in the cockpit doing something I’ve not seen for years. Each is reading a book. No iPhones in sight. I’m grinning. It’s a nice trip.

I know this harbor, Deshaies, all too well. The bottom is hard and deep. The wind, now calm, can blow something fierce down the mountainsides. There are stories of charter parties ashore for dinner who discover too late that their boat has dragged and drifted out to sea, the French Coast Guard called to tow it back. Then there’s the northerly swell. When a nor’easter is lashing the New England coast back home, the swells reach all the way down here. I was here not so long ago when the swells drove me back to Antigua. All is quiet now.

This is the tropical village every sailor dreams of. Surrounded on three sides by tall cliffs and mountains, this small, one-street town runs along the beach. There are cafes, restaurants, three markets, a boulangerie, a farmer’s fruit stand, even a rental-car agency. There are trails to hike, a cascading river in which to swim, a large botanical garden to explore and one of the longest beaches in the Caribbean, just around the corner.

“What do you want for your birthday?” Julie asks Ren the next morning. It’s the 23rd of December—Ren’s 21st birthday—and we are all ashore for breakfast at the local cafe.

“I want to go scuba diving.” Ren recently passed her deepwater dive test at the Academy and is eager to dive in the warm tropical waters.

“The Cousteau Underwater Park is 8 miles down the coast,” I suggest.

“Can we go?” she asks.

We do. It’s midafternoon when we arrive in the narrow anchorage. When we reach 30 feet of water, I shout to Ren to drop the hook.

“Farther in, Dad,” my daughter demands. “Over there.” This goes on for a few minutes.

“Who is the captain on this boat?” I shout from the helm.

“Dad! Your Coast Guard license expired 10 years ago. If anyone has authority, it’s me.“ She’s got a point; she has a valid license. Reluctantly, she releases the anchor and we are parked. The gang goes ashore and signs in for an afternoon dive trip to the park that surrounds nearby Pigeon Island. I remain aboard for a nice nap.

Just as dinner is ready, after everyone has returned from the dive trip, I notice that the depth sounder reads 60 feet.

“All hands on deck,” I shout, starting the engine.

“Can’t this wait until after dinner?” Julie growls.

“Nope. Now! The anchor has come free. We are drifting back out to sea.” No time for an argument.

“Ren! Come back here and take the helm. I’ll handle the anchor.” We switch places, and Ren finds us a spot in shallower water. I release the chain as she backs down, watching the chain angle out; when it tightens, I give her a clenched-fist sign. Reaching over the bow, with my foot on the chain, I feel the chain tighten, jump, then set. OK. I feel better. Daughter did well. Now she’s the captain.

HAPPY HOLIDAYS

It’s Christmas morning back in Deshaies. Julie takes these holidays seriously. She’s English. As we all stumble into the main cabin, there on the saloon table is a Christmas tree; well, not a real tree. Julie decorated a Guadeloupe pineapple with a string of battery-operated lights. The table is strewn with presents she’s brought down in her luggage, each now wrapped in brown paper from used shopping bags. Sailors are a resourceful lot.

We leave Deshaies at 0830 three days later, bound for the Saints—a group of small islands 8 nautical miles south of Guadeloupe. As we motor a mile or two offshore, the mountains seem to march along with us. Valleys recede into the interior revealing still, high mountains beyond. Cars move along the coastal road. Life and business goes on ashore.

As we round the southern tip of Guadeloupe, we encounter a 15-knot southeasterly breeze. Right on the nose. As we power into the wind and chop, the Saints turns from dull gray to musty green to a vibrant emerald as we creep closer. It’s 3 o’clock in the afternoon when Ren finds us a spot in 30 feet of water. It’s her call now. I lower the anchor and chain as she backs down. The 35-mile trip from Deshaies took us seven hours.

On December 30, the kids and I are up with the sun and head ashore. Havana wants to photograph the island with the drone, in the morning light. Off he goes.

“Come on, Dad,” Ren pleads. “Let’s hike up to the fort.” I look up at the steep hill over the village and groan. This early in the morning, we have the village of Le Bourge to ourselves. In two hours, the ferries from Guadeloupe will deposit hordes of tourists. We wander along the main street, lined with colorful shops, boutiques, restaurants and bike shops, all now closed. We walk up into the residential area, houses packed close, built into the hillside. Steeper and steeper, the harbor below opens up, and we can see The Dove on the far side. Above us, we reach the massive Fort Napoleon. It sits, quietly, as it has for 200 years.

As we depart from the Saints later that day, a perfect 15-knot easterly breeze fills in. It’s 20 nautical miles across to Portsmouth, the town and anchorage on the northwest tip of Dominica. It’s 5:20 p.m. when we drop sails and the hook amid another 50 yachts.

We are looking for Albert, a local “boat boy.” At 50, he’s one of the leaders of the Portsmouth Association of Yacht Security, a club of helpful locals. Albert shows up the next morning, and we ask him how we can arrange to take a trip into the jungle up the Indian River.

“I can do dat, mon. Dis afternoon, you come.” We do.

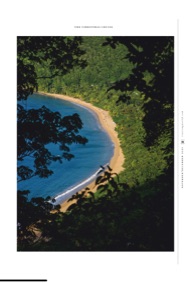

We pile into Albert’s seaworthy 25-foot open boat and head into the jungle. There’s a 50 hp outboard pulled up on the transom, so Albert, seated in the stern, ships two long oars, and off we go, slowly. The Indian River weaves inland for miles, lined on both sides by an impenetrable jungle. Vines meet overhead to create a tunnel. Colorful boats, like Albert’s, also ply the river this afternoon. Albert, seated in the stern, faces forward pushing his oars while maintaining a running commentary. We learn of the vegetation, lizards and birds along the shore. We arrive all too soon at a dock built into the riverbank. We disembark to find a tropical flower garden and a cafe serving bowls of coconut rum punch.

As darkness descends, we glide back down the river. The only sounds we hear are birds and the occasional swish of one of Albert’s oars. We will later all agree, it was a magical experience. We thank Albert for sharing his island and stories of his life on Dominica.

The next morning, on the first day of January 2020, we are off early in a rented jeep into the, well, heart of darkness. We head east, up into the hills, with Ren as navigator. I’m the helmsman. The paved road climbs up into the mountains, along deep gorges, over cascading rivers. Vegetation drapes from craggy ledges, covering whole mountainsides; it climbs trees, hangs from limbs. A rain shower comes and quickly goes. The road descends, winding along the eastern coast, in and out of coves, through small villages, by beaches and past the small airport. There’s a Carib village here somewhere, home to the last remaining native tribe. We find it, down a steep road toward the sea. Pulling over to allow a car coming up, I puncture the left front tire. The air hisses out. We have a flat. I park off the road and the family continues on foot, leaving me to change the tire.

Back on the road. Midafternoon. Ren finds a shortcut through the mountains. All is fine, until the paved road peters out. It turns to dirt, then gravel, with grass growing down the middle. I’m a nervous wreck. There’s no spare tire now. We finally emerge back into civilization. I need a drink.

CHRISTMAS WINDS

The dinghy is on deck, sail cover off and folded, engine on and anchor up. It’s the second of January. We are underway out of Portsmouth at 0700. Our destination: the anchorage off Saint-Pierre, on Martinique.

As we pass Scotts Head, at the southern tip of Dominica, Martinique comes into view on the horizon and a nice breeze fills in, easterly, 12 to 15. Ren unrolls the jib. I turn off the engine. The boat leans into a 10-degree heel; we’re moving along nicely at 6.5 knots on course for Saint-Pierre. This is uncommonly nice.

Late afternoon, we anchor on a narrow shelf just off the town below the towering Mount Pelee. This now-dormant volcano blew its top in 1902, and a pyroclastic flow swept down the mountainside, killing 30,000 residents, in seconds flat. The only survivor? A lone prisoner in jail. Today, Saint-Pierre is a quiet residential town, no cruise ships; only a few yachts stop in the anchorage. The sunsets turn the tightly packed cottages along the beach crimson and gold.

There was a nice French bistro here 10 years ago. Is it still here? The family elects to go see. It is, and we tuck in. The food is French—local fish in a white sauce laced with garlic. We are all in good spirits. The family together, perhaps for our last cruise together? Who knows.

The next morning, the family is ashore early with cameras. Havana and I find a spot from which to fly the drone, Ren wanders the streets with her new iPhone 11.

“Havana,” I instruct, “make sure you get The Dove in the picture as you fly past.”

“Dad. Don’t you have photographs you can find without bothering me?” My son has just given me my marching orders. As did my daughter a few days earlier. I can see he wants his independence. My role as a parent, their teacher, is changing. Time marches on.

Back aboard, we up-anchor and head to Sainte-Anne, at the southern tip of Martinique.

Dominica’s mountains might be impenetrable and dramatic, but Martinique’s are inviting and productive. Fields of sugar cane, orchards, and farmlands spill down the gentle slopes. We round a headland, turn east, and pass between Diamond Rock and the mainland. Ahead we see a line of anchored sailboats so thick that you can’t see the beach on Sainte-Anne, a small beach town with an open roadstead. There are more than 200 boats anchored here. I counted them.

The end of this little journey is in sight.

But first, there’s the village of Sainte-Anne to explore. The long, well-maintained dinghy dock is packed, the sidewalks filled with French tourists, vacationers and a few sailors. The latter all have deep tans and faded shorts. The main street is lined with colorful shops, including a boulangerie, two food stores, and an open-air produce and fish market. There are half a dozen cafes, restaurants and bars along the beach in this small, well-kept village. And there are vacant beaches nearby to explore, clear water in which to swim, and a Club Med nearby. La Marin, one of the Caribbean’s busiest marine centers, is a few miles away, with more services than I’ve seen in any port, anywhere.

Our last morning together. The family loads up the dinghy with duffels and bodies, and I drive them to the dock. A cab is waiting for the hourlong drive to the airport. When I return to The Dove, something is amiss. The wind is blowing like stink. There’s a nasty chop. The rigging whistles, and the whole boat is vibrating. My clan is gone. The Christmas winds have arrived.

David L. Lyman is a seasoned mariner and professional photographer, and, when not roaming the Caribbean, is based in Maine. ■

One of the highlights of our journey was a trip into “the heart of the jungle” up Dominica’s wild Indian River with the trustworthy “boat boy” Albert as our friendly, knowledgeable guide.

The Saints - a small group pf islands south of Guadeloupe