`

No Wind

Occasionally there are days of no wind at all. Larry Tyler, owner and skipper on the charter yacht The Dove, has been sailing these islands for more than 30 years. Recently, he told me, “The only thing that comes to mind is that every year once or twice, the winds die down completely and then suddenly you get a westerly wind blowing you on to beach, if you are anchored too close.

Last April, during the Antigua Classic Yacht Regatta, the first day’s race was a drifting competition in calm conditions. The sea was like a mirror.

The Winds

in the West Indies

Story and Photois by David H. Lyman.

First published in Cruising World’s Caribbean Current Newslettwr, September 4, 2024.

The biggest mistake you can make is to let down your guard when sailing in these islands.

When I first sailed the Lesser Antilles islands in the late 1970s, I listened to the morning weather broadcast from Radio Antilles. It came on every morning at 8:05, from an AM radio station on Montserrat.

“Today’s weather will see winds south of east to north of east, from 12 to 18 knots, with higher gusts. Occasional showers. No significant change is anticipated over the next 48 hours.”

I swear, it was the same recording we heard every morning.

The trade winds do blow, with predictable regularity, from the northeast to southeast all year long. There’s an occasional deviation: the passage of a hurricane or a few days of calm. There is a wet season in the summer, a dry season in the winter, and short periods of stronger winds—the Christmas winds—in late December through early January.

Still, after 25 years of sailing here, here are my words of warning: You can get lulled into complacency amid these islands. It’s part of their charm. But then you pay for it when the winds kick up.

The Christmas Winds

A few years ago, at the end of a delivery from Antigua, I had anchored off the charming village of Sainte-Anne on Martinique. Something awakened me at first light. Still half asleep, I plodded to the companionway.

When I emerged into the cockpit, the weather was blowing like stink. I looked through the dodger window to see hundreds of whitecaps marching toward us. They were only a foot or so high, but they were steep, deep and sharp. They didn’t really bother the 54-foot sloop I was on, but the dinghy astern was dancing a jig.

Then, I heard the surrounding noises. There was a hum throughout the boat as the wind strummed a tune in the rigging, rising in pitch as the wind increased. Other noises mixed in: the snapping of the ensign astern, the flapping of the sail cover, the high-pitched whine of the wind generators above the aft arch.

I switched on the nav instruments. The wind indicator hovered between 20 and 25, then scooted up to 30 as a gust hit. This is a moderate gale on the Beaufort scale.

It was late January. The Christmas winds had arrived—late.

I thought it would blow like this for a few days, but rarely a week. It’s all academic, I told myself. What were the practical implications? Getting ashore in the dinghy would be a wet ride. I was reluctant to leave the boat on its own.

By the time I looked again, the RIB tied off astern was bouncing like a pony trying to throw its halter. The painter couldn’t take too much more before it would tear the ring out of the boat. I had elected to anchor way out at the edge of the field, for privacy and an unrestricted sunset view. That means the easterly wind had a longer fetch to build up these nasty waves.

I hauled in the RIB and tied on a longer painter, figuring more scope might reduce the snapping. It didn’t. Closer in? That didn’t work either.

Other boaters had come to the same conclusion. We all needed to haul our RIBs out of the water. Some had davits; others, like me, had to use a halyard or stow the thing on deck.

That done, I checked the anchor chain. As the boat was driven back in a gust, the anchor chain straightened out, and the snubber came taught and stretched out. I had dived on the anchor when I first set it and was confident it would hold, but I wondered if I might awake one morning on my way to Honduras.

I watched as two French bareboats attempted to re-anchor. It didn’t go well. The wind was driving them sideways so fast that the anchors never had a chance to set.

The Christmas winds—we’d all just have to sit tight.

Island Effects

The tall mountains of the larger Caribbean islands block the trade winds, creating a wind shadow to leeward. These shadows can extend out to sea for 10 to 20 miles, which means a lot of motoring as you make your way south or north along the island’s flank. It can be a welcoming experience after bashing through the open Atlantic between the islands.

Along the western shore of Guadeloupe, the moist trade winds are blocked by the 6,000-foot tall mountains, creating calm conditions in their lee. At night, however, cool air from the mountaintops descends down and funnels through those narrow valleys, blowing west. These are known as katabatic winds. David H. Lyman

As I was sailing north from the Grenadines up to Antigua last April, I was aboard Richard Thomas’s Reliance 44 cutter. We’d left Prince Rupert Bay on Dominica that morning and were sailing north, west of Îles des Saintes. It was mid-afternoon when we ran into Guadeloupe’s wind shadow. We were about 5 miles offshore and had to proceed under power.

Then, I spied three sailboats, close in with the shore, sailing north, their sails full. Could there be a westerly sea breeze at play?

“It is possible to make way under sail in the lee of the High Islands?” Don Street writes in his Transatlantic Crossing Guide (my copy is from 1989). “Most sailors assume there will be a total lull close to shore, so they pass 3 to 4 miles off—which is just where you find absolutely no wind. But there is a way to skirt along the lee shore of these high islands, which I discovered in a book of 18th-century sailing directions. There are three recommended ways of passing the islands: at seven leagues (21 miles offshore) or else close enough to be within two pistol shots of the beach.”

The historian Dudley Pope explains that a pistol shot was a recognized term of measurement in those days and appears frequently in accounts of naval battles. It’s the equivalent of 25 yards.

“So stay within 50 yards offshore,” Street continues. “Which may be a bit closer than you want, but not by much. You stand a good chance of enjoying a smooth, scenic sail the length of the high island. The best time to try this is between 1000 and 1600. After 1600, the breeze falls off rapidly.

He continues: “During the day, as the land heats up, you’ll sometimes pick up a westerly onshore breeze right up to the beach, counter to the trades, which continue to blow to the west higher up. Alternately at night, the cool air falls down off the hills, often providing a beautiful moonlight sail along the beach.”

This is one of the tricks savvy sailors use when sailing along Hispaniola and Puerto Rico’s north coasts.

“Dawn and dusk are the only times when there is absolutely no wind in the lee of these islands.” Street goes on. “I would say that, except for these times, you’ll be successfully sailing the lee shore about 75 percent of the time. Of course you can always sail up and down the islands, passing to windward of them.”

Night Winds

It’s those night winds Don writes about that concern me most.

Anchored in the delightful harbor of Deshaies on the northwestern tip of Guadeloupe, I’ve experienced these night winds numerous times. All is fine as you nestle in at anchor, and then the winds begin around 2 a.m. Easterly blasts of cool air traveling at 30 knots barrel down through the mountain valley, and through town and the harbor, testing your ground tackle and anchoring skills.

I lay awake in the cockpit, one eye on a fixed light ashore to see if we were dragging.

“These are katabatic winds,” Chris Doyle told me recently. “Heavy cold air at the mountaintops slides down the slopes in the valleys and out to sea, resulting in a westerly airflow at the sea surface.”

Island Wind Refraction

Refraction is the phenomenon by which waves—light, radio, sound and sometimes ocean waves, currents and wind—bend when meeting an obstacle and curve away from their original path. That obstacle can be an island.

When sailing south one season on Searcher, my 57-foot Bowman ketch, we motored down the lee shore of Dominica with plans to anchor in Saint-Pierre on the northeast tip of Martinique for the night. As we approached the southern tip of Dominica, we began to experience a south-southeast wind, and I fell off to the west southwest. Swells were behaving the same way.

Five miles later, the wind and waves started to come back to the east, and we corrected our course to the south. By this time, we were too far west and in no position to fetch Saint-Pierre. Then, I figured we’d experience the same effect, in reverse, as we reached the northern tip of Martinique. The winds did bend to the north, and we were able to correct our course and make it in.

This effect occurs around many of the islands’ northern and southern tips. Tides also play a part. Even if only a foot or 2, a foul tide can also kick up a nasty chop when running counter to the prevailing wind.

During last April’s voyage, north up the coast of Guadeloupe, we decided not to duck into Deshaies for the night. We could make the anchorage off Jolly Harbor on Antigua by midnight. As we were rounding the northern tip of Guadeloupe, we encountered confused seas and strong, gusty winds. It was frustrating and uncomfortable.

I’ve experienced this before; the winds get channeled between the main island landmass and two small islands off the tip of Pointe Allegre. After a while, things settled down, and progress could be made. By the time we got the anchor down off the beach in Jolly Harbor, it was 2 in the morning.

Hurricanes

Every summer and fall, from June through mid-November, these islands are visited by a series of tropical waves. Before some of these waves reach the islands, they may turn into tropical storms with winds as high as 70 knots. As they accumulate energy and build strength, they turn into hurricanes, with winds in excess of 70 knots.

The whirling winds, rain, surges and waves pass through the island chain quickly, normally moving along at 12 knots. They come and are gone in less than a day, but the devastation they leave behind can be extreme.

Hurricane Beryl came through the Grenadians last July, destroying 70 percent of the homes on Carriacou and Union Island, and severely damaging the remaining 30 percent. The peak of hurricane season is September, after the summer sun has heated up the Atlantic surface water, leading to enhanced evaporation, the fuel that drives a hurricane.

Thankfully, these days we have excellent sources to find out what’s coming .

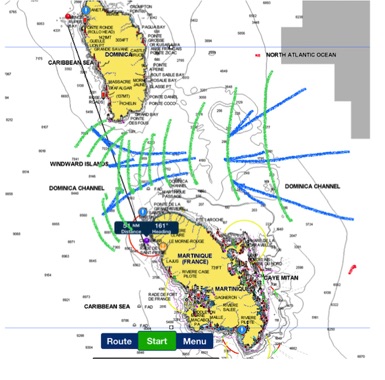

This Windy app graphic shows the wind shadows behind larger islands of Guadeloupe, Dominica, Martinique, St. Lucia and St. Vincen to the leeward of each island.

Donald Ward’s 47-foot Freya, from the Antigua Yacht Club, drifts along on a becalmed sea during the Classic Regatta in late April.

Sailing north along the western coast of Dominica, an afternoon westerly breeze set in as the land heated up, drawing a sea breeze.

The author heads aft to check the dinghy that's dancing a jig.

A stiff breeze finds us in the anchorage at St. Anne, Martinique

The trade winds moisture is backed to the east of Mount Pelle on Martiniaue.

Motoring through a windless sea in the Grenadians.

Reefed down, running bewtween the islands.

Island Wind Refraction.

Wreckage following Hurricane Hugo in Hurricane Hole on St. John, USVI, 1989.